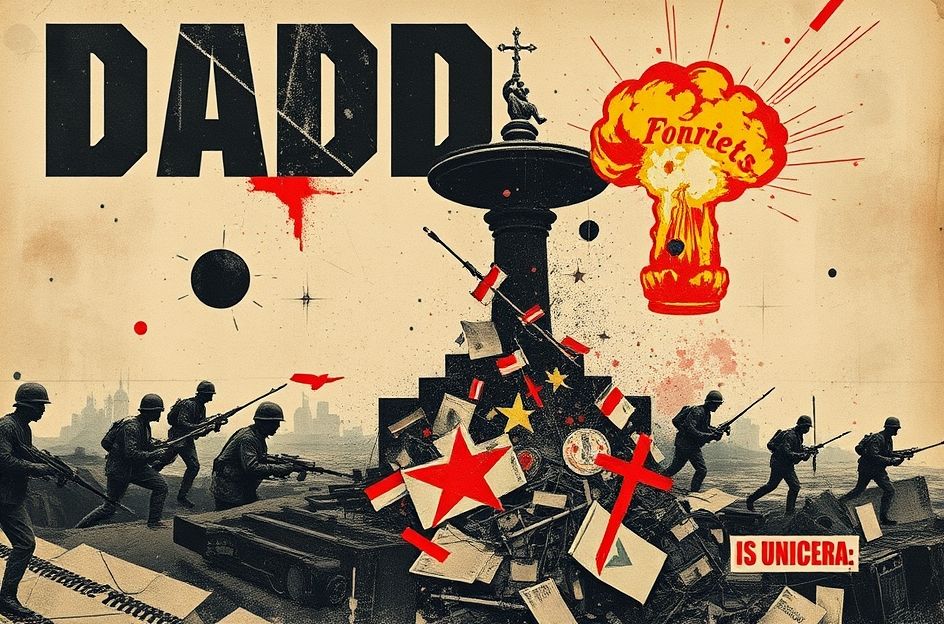

Dadaism emerged as an artistic movement during the tumultuous years of 1916-1920, a direct response to the devastation and disillusionment of World War I. Dadaists vehemently opposed the war and the traditional artistic values they believed had failed to prevent it. They saw art as complicit in a civilization that had descended into barbarity, protesting against established notions of beauty and order.

Dadaist activities included organized demonstrations, the creation of propaganda, and the publication of manifestos and brochures denouncing the war’s cruelty. They drew inspiration from figures like Arthur Rimbaud, Max Jacob (who tragically died in a Nazi concentration camp), and Guillaume Apollinaire. They launched journals filled with anti-war and anti-establishment articles, often employing satire to highlight the absurdity of the conflict. Performances in venues like Cabaret Voltaire served as platforms for theatrical critiques of World War I. Tristan Tzara, a leading figure in the movement, disseminated articles in various European newspapers, aiming to expose the full horror of the war.

Like Dadaism, Surrealism also arose from anxieties surrounding World War I. Both movements shared a desire to explore the irrational and the surreal as a means of confronting the trauma of the conflict. Surrealism inherited Dada’s pessimistic and revolutionary spirit. Dada’s core principle was to prioritize activities and theoretical exploration over the creation of traditional representational art, embracing irrationality and chance. Artists like Jean Arp and Marcel Duchamp explored these concepts through methods like Arp’s “Law of Chance,” where he dropped paper scraps and glued them where they landed.

Surrealism adopted Dada’s emphasis on the subconscious and uncontrolled thought processes in artistic creation. They valued dreams (as seen in the work of Salvador Dalí), intuitive associations, and chance encounters (exemplified by Max Ernst). Both Dadaists and Surrealists incorporated elements of absurdity and illogic into their works.

A key link between Dada and Surrealism is that several prominent Dada artists and poets, including Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Tristan Tzara, transitioned into Surrealism later in their careers.

Roberto Matta’s “Invasion of the Night,” a large oil painting created in 1940 after his move from Paris to New York, exemplifies Surrealist principles. Executed in a biomorphic or abstract style, the painting features organic shapes, soft color transitions, and a warm palette to evoke a dreamlike atmosphere. Its composition, reminiscent of a chessboard formed by the interplay of yellow and blue-green forms, generates a sense of unease. The luminous saffron color, punctuated by white spots, creates the unsettling impression of holes in the canvas. Tiny red objects scattered throughout heighten the feeling of anxiety, yet the artwork’s intricate details and captivating patterns hold the viewer’s attention, drawing them into its surreal world.