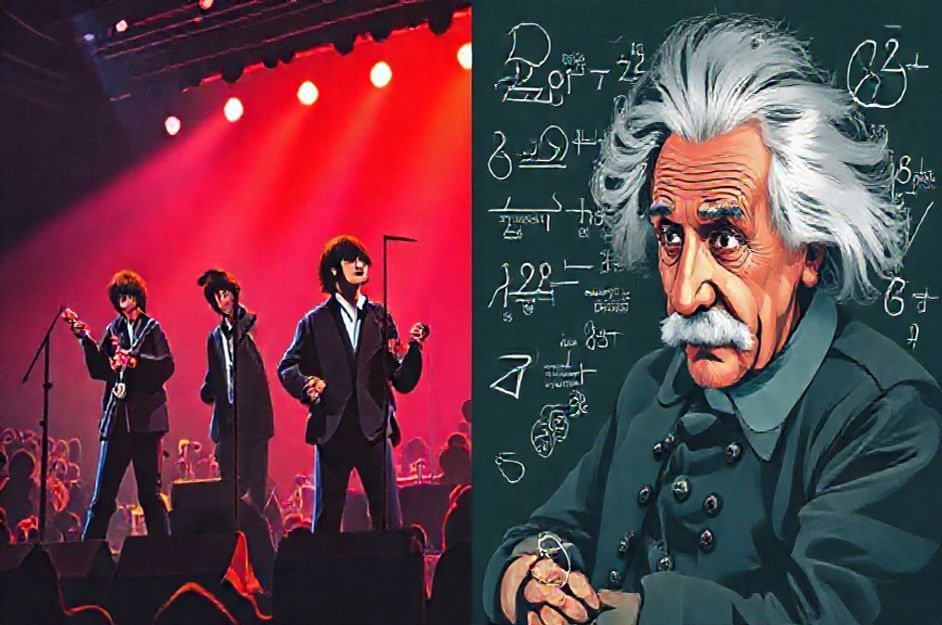

Why did the Beatles earn more in a single year than Albert Einstein did throughout his entire career? It’s a question that prompts immediate, yet incomplete answers.

One might argue about the scarcity of talent: How many bands rivaled the Beatles? But then, how many scientists reached Einstein’s level? Rarity alone doesn’t explain the vast difference in financial reward.

A more compelling explanation lies in accessibility. Music, sports, and movies are easily understood by the general public compared to physics. Mastering the rules of a sport requires minimal effort, leading to mass appeal for entertainment and, consequently, greater revenue. This broad appeal translates into extensive media coverage and the creation of marketable personal brands, like David Beckham or Tiger Woods.

However, the internet’s creation presents a counter-argument. Why didn’t any of the scientists behind its development become billionaires, despite its widespread accessibility?

Perhaps a less comfortable truth is at play: a societal resentment towards intellectual elitism. People may harbor a hidden animosity towards the perceived exclusivity and complexity of modern science. This resentment can manifest as anti-intellectualism, resistance to technological advancements (Luddism), and even a proud display of ignorance. Many prefer the allure of the esoteric and pseudo-sciences over genuine, challenging scientific pursuits.

Consumers often perceive entertainers as relatable and “good.” The possibility of achieving instant celebrity feels attainable, while becoming an Einstein seems insurmountable.

Science, therefore, carries an image of being austere, distant, inhuman, and demanding. The relentless pursuit of truth can even provoke suspicion among those who don’t understand it. Popular culture frequently portrays science as dangerous or evil, citing examples like genetically modified foods, cloning, nuclear weapons, toxic waste, and global warming.

Intellectuals and scientists are sometimes viewed as outsiders, eliciting fear rather than admiration. Underpaying them could be seen as a way to diminish their influence and control potentially subversive activities.

The anti-capitalistic nature of scientific ethics further contributes to this financial disparity. Scientific knowledge and discoveries are meant to be shared freely with colleagues and the world. The benefits of science belong to the community, not solely to the individual researcher. Of course, this ideal is often complicated by corporate interests, where firms and universities hold patents and profit, but those profits rarely trickle down to the researchers themselves.

Furthermore, modern technology has transformed intellectual property into a public good. Books, texts, and scholarly papers are non-rivalrous and non-exclusive. The very idea of originality is challenged by reproducibility. What’s the real difference between the first and millionth copy of a scientific treatise?

Attempts to counteract this trend, such as extending copyright laws or fighting piracy, often prove futile. Scientists and intellectuals not only earn modest wages but also struggle to supplement their income through book sales or other forms of intellectual property.

As a result, the number of individuals pursuing intellectual endeavors is declining. We may be entering a new era of diminished innovation, replaced by a focus on shallow “pulp” culture. Media attention is largely devoted to sports, politics, music, and movies.

It’s increasingly difficult to find substantive coverage of science, literature, or philosophy outside of specialized channels. Print and electronic media often avoid intellectually demanding content, and literacy rates have declined, even in developed nations.

In this environment, economic policy is influenced by celebrities, political leadership is entrusted to actors, reading tastes are shaped by talk show hosts, and the future is guided by entertainers.